Elmes love the Vines, the Vines with Elmes abide – a modular skirmish board set during the Second Punic War I

Ageinst him where he sat

Ov. Met. 14.661-665

A goodly Elme with glistring grapes did growe: which after hee

Had praysed, and the vyne likewyse that ran uppon the tree:

But if (quoth hee) this Elme without the vyne did single stand,

It should have nothing (saving leaves) to bee desyred: and

Ageine if that the vyne which ronnes uppon the Elme had nat

The tree to leane unto, it should uppon the ground ly flat.

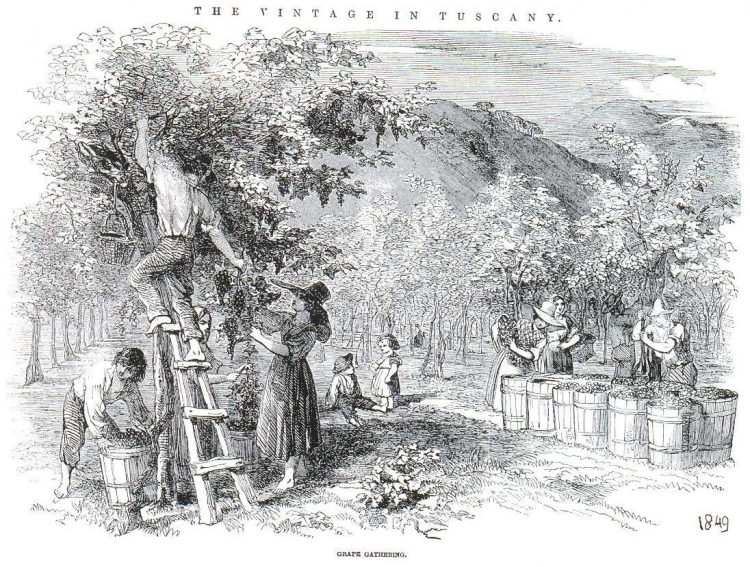

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BCE to 17/18 CE) is famous for his love poems (Amores) and his mythological narrative Metamorphoses. In the short piece above, taken from the latter work, he describes casually a then very common form of viticulture and uses it as a metaphor for marriage. He already uses this simile in his Amores in the well-known phrase “Elmes love the Vines, the Vines with Elmes abide” (Ov. Am. 2.16.41). The relationship of vine and elm tree (or growing wine on trees as a support in general) is a long-standing one and continued in Italy well into the 20th century (cf. Fuentes-Utrilla, López-Rodríguez & Gil, 2004).

Nowadays this form of viticulture is very uncommon, but nevertheless sparked my interest. More importantly it also spawned a new project – the very raison d’être for this post: a modular skirmish board set during the Second Punic War featuring a villa rustica complete with vineyard, olive grove and orchard.

In a multi-part tutorial I will guide you through the creation process from the early planning stages to the final piece. In this first part we will look at the design of the modules, historical considerations when it comes to depicting a Roman vineyard complete with villa rustica and finally we will also have a look at some Agema miniatures to provide some suitable skirmish forces.

Initial considerations – theming the board

Why do I want to depict a heavily cultivated area? For a skirmish level game it is very likely that foraging missions, ambushes and even smaller engagements will have taken place in cultivated areas as opposed to featureless plains. Especially so in mainland Italy. Farms will have been a target for foraging and pillaging or might have provided a tactical advantage. It follows that with such a theme one can depict a great variety of scenarios. Using such a landscape in other periods is no problem either. As long as features on the actual boards won’t give away the ground scale one could also use the boards for 15mm.

However, now you may wonder if the gaming surface will not be obstructed with rows of vines and trees. Well, given that I want to go for a form of viticulture that is based on trees as a support the gaming board will be quite unlike what you would expect from a modern vineyard. We won’t have rows of low growing vines, nor will we have wine arbours obstructing the gaming surface. Any tree is supposed to be removable and magnetised. It follows that we can have open ground with light rolling hills or a densely cultivated area, such as an olive grove, orchard or vineyard. This gives us maximum flexibility and also allows us to depict a lush oak forest if we desire or a single tree in an open field.

Naturally there will be some compromises. Water features, roads and clearings will need to be shaped and the placement of magnets will limit configurations. Finally any settlement or villa rustica may need to be a fixed element on a module. While it may be possible to make them removable, this could result in a less pleasing appearance or even gaps between walls and ground.

The design – accurate, sturdy, flexible

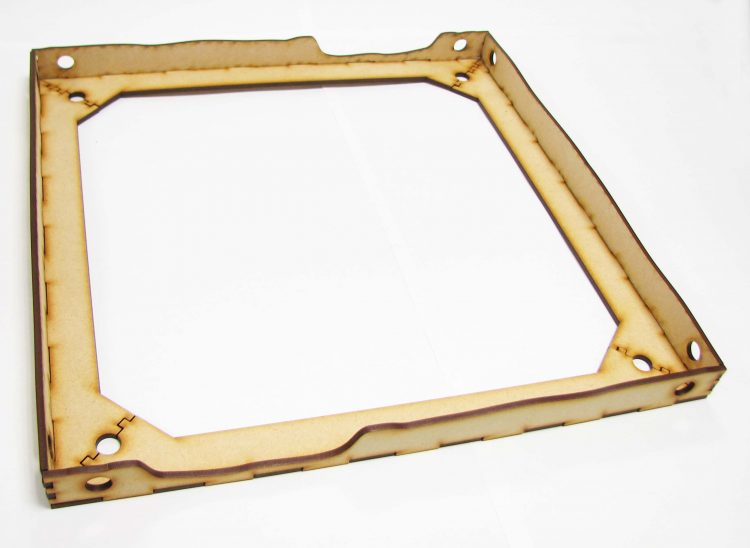

We have an idea, no we need to think about the design. Given this is my second attempt at designing a modular gaming board (see my Crypt of the Damned tutorial) I had a feeling for what worked and what did not. The basic idea is to have a core of extruded polystyrene, protected by MDF on its bottom and plywood on its sides. Terrain features will be built up with more foam or sculpted onto the surface. This will then be covered in acrylic modelling paste and sand. This way we can solve most problems that gaming boards made of extruded polystyrene face without adding significant weight.

Most important for any modular project is accuracy or your modules will not fit together. Cutting MDF by hand is a hellish endeavor. So to save my sanity I used a laser cutting service to cut profiles for the bottom and sides. I also wanted to integrate some pegs and slots to make assembly of the pieces easier and to assure that while glueing them together no inaccuracies are introduced.

Making the module 300mm x 300mm x 20mm is a good compromise between maximizing the number of possible combinations, easy handling of a module and enough depth to sculpt a river or pond. 300mm fits also well in the standard gaming table sizes, thus we can easily extend the modular gaming board to get any size required. For starters I just want to make four modules to get a nice skirmish sized board of 600mm x 600mm.

I got some styrofoam sheets measuring 1250mm x 600mm x 10mm, but any size works. It makes sense to get a piece that is large enough to get a few 300mm x 300mm pieces out of one sheet. Just have a look at your local hardware and construction store.

To place trees, fences, walls and even houses, I will embed steel tacks in the surface allowing all elements to be securely placed on the board using rare earth magnets. This will require some experimentation to see what looks natural and how many steel tacks per module are necessary.

Historical background – how to grow wine on trees

It might not come as a surprise that we have rich literary evidence what concerns viticulture in the ancient world. Being such an important industry, we have a variety of authors dedicating entire books to the art of agriculture and giving advise how to best grow vine and manage a farm. Cato the Elder‘s De Agricultura, Columella‘s De re rustica and book 17 of Pliny the Elder‘s Naturalis Historiae come to mind. Both Cato (Agr. 30.1; 33.1) and Columella (Rust. 3.13) describe a way to grow wine we are more accustomed with: long rows of vines supported by wooden stays, bound up with reeds or supported by arbours. The farm was a microcosmos with all the wooden supports and reeds needed grown on-site.

Pliny the Elder on viticulture – placement of trees and roads

However, for growing wine on trees we will resort to Pliny the Elder’s description, which is part of his much longer treatise on growing wine (Plin. Nat. 17.35). First we learn about the proper arrangement of elm trees as a support for vines:

In arranging trees and shrubs for the support of the vine, the form of the quincunx [each at an angle with the other] is the one that is generally adopted, and, indeed, is absolutely necessary: it not only facilitates the action of the wind, but presents also a very pleasing appearance, for whichever way you look at the plantation the trees will always present themselves in a straight line.

Plin. Nat. 17.15

This we need to keep in mind when placing the steel tacks. They need to reflect some cultivation of the trees instead of being an unchecked grown forest. If we want to use a module as both, cultivated area and forest, we need to place more tacks to allow for proper placement of trees.

Pliny also recommends that the

vineyard should be bounded by a decuman path [going from east to west] eighteen feet in width, sufficiently wide, in fact, to allow two carts to pass each other; others, again, should run at right angles to it, ten feet in width, and passing through the middle of each jugerum [a Roman measuring unit, about 0.65 acres]; or else, if the vineyard is of very considerable extent, cardinal paths [at an angle to the decuman paths] may be formed instead of them, of the same breadth as the decuman path. At the end, too, of every five of the stays a path should be made to run, or, in other words, there should be one continuous cross-piece to every five stays; each space that is thus included from one end to the other forming a bed.

Plin. Nat. 17.35.22

For our purposes it makes sense to depict the edge of a vineyard with a decuman path and some smaller paths going through it. If done in an unobtrusive way these paths can also function as a road, once again to preserve flexibility.

Ways to grow wine in the ancient world

Pliny elaborates in great detail on different ways to grow vine including growing it supported by elm trees:

The experience of ages, however, has sufficiently proved that the wines of the highest quality are only grown upon vines attached to trees, and that even then the choicest wines are produced by the upper part of the tree, the produce of the lower part being more abundant; such being the beneficial results of elevating the vine. It is with a view to this that the trees employed for this purpose are selected. In the first rank of all stands the elm […]

Plin. Nat. 17.35.23

They must not be touched with the knife before the end of three years; and then the branches are preserved, on each side in its turn, the pruning being done in alternate years. In the sixth year the vine is united to the tree. […] The top of the elm is lopped away, and the branches of the middle are regularly arranged in stages; no tree in general being allowed to exceed twenty feet in height. The stories begin to spread out in the tree at eight feet from the ground, in the hilly districts and upon dry soils, and at twelve in champaign and moist localities. The hand of the trunk ought to have a southern aspect, and the branches that project from them should be stiff and rigid like so many fingers; at the same time due care should be taken to lop off the thin beardlike twigs, in order to check the growth of all shade.

We get a good idea how the elm trees are pruned to take the vines. I could see a tree three times as high as a 28mm miniature with strong branches spreading out in all directions, but less so thinner branches. We also read recommendations for intervals between the trees of twenty feet and a number of three to ten vines per tree. Pliny also explicitly mentions that the vines can protect themselves from injury by animals due to their height making it not necessary to enclose the vineyard with walls, hedges or ditches (Plin. Nat. 17.35.23). This is significant and makes our job easier as we do not have to take fence posts into account when placing the steel tacks.

Pruning and training the vines

Pliny also mentions two ways of training the vines upon the tree:

The plan, however, of growing from layers in baskets set upon the stages of the tree is the most approved one, as it ensures an efficient protection from the ravages of cattle; while, according to another method, a vine or else a stock-branch is bent into the ground near the tree it has previously occupied, or else the nearest one that may be at liberty.

Plin. Nat. 17.35.23

He then proceeds to describe different ways of pruning and training the vines in Italy and Gallia, in the latter case going so far as fastening the branches of different trees together for the vines to grow in unison:

In Italy the pruning is so managed that the shoots and tendrils of the vines are arranged so as to cover the branches of the tree, while the shoots of the vine in their turn are surrounded with clusters of grapes. In Gallia, on the other hand, the vine is trained to pass from tree to tree. On the Aemilian Way, again, the vine is seen embracing the trunks of the Atinian elms that line the road, while at the same time it carefully avoids their foliage. […]

In the Gallic method of cultivation they train out two branches at either side, if the trees are forty feet apart, and four if only twenty; where they meet, these branches are fastened together and made to grow in unison; if, too, they are anywhere deficient in number or strength, care is taken to fortify them by the aid of small rods.

In a case, however, where the branches are not sufficiently long to meet, they are artificially prolonged by means of a hook, and so united to the tree that desires their company. The branches thus trained to unite they used to prime at the end of the second year. But where the vine is aged, it is a better plan to give them a longer time to reach the adjoining tree, in case they should not have gained the requisive thickness; besides which, it is always good to encourage the growth of the hard wood in the dragon branches.

Plin. Nat. 17.35.23

This gives us quite a number of options depending which locality we would like to model. As our setting is the Second Punic War, mainland Italy, but also Spain and Africa ar suitable localities. For starters I will model the elms with eight to ten vines growing around the trunks and branches and maybe at a later stage consider the Gallic way to grow them.

Now we know how the trees are supposed to look like, but what about the villa rustica?

Villa rustica – all roads lead to Rome

For the design of the villa I decided to use a historical example: one of the Via Gabina villae, more precisely Villa 11. Based on numismatic evidence the first phase of this villa can be dated between 217 BCE and 200 BCE, so a perfect match for the Second Punic War. It is a relatively humble site that is well documented and researched by Walter M. Widrig (see his website for a scale model of the first phase as well as a floor plan).

His online publication on this villa and two other sites is a treasure drove for reconstructing the look of a Middle Republican villa rustica. It is much more humble than the lavish later examples we know from southern Italy, for instance the Villa Boscoreale. The villa was a victim of the Vesuvius eruption in 79 AD, thus it is well-preserved but naturally much later than the Punic Wars. Nevertheless, it is an example for the significant changes that took place both in architecture, size and economic significance of the villa rustica and villa urbana in the imperial period (follow this link for a scale model of the villa; see also Becker (2013) for an overview of current scholarly debates what concerns the Roman republican villa).

Given that the Villa 11 is well documented and floor plans exist, building a scale model should be relatively easy. Its U-shape and comparatively small dimensions make it well suited to fit on one or two modules. Viticulture and villae – check. Onwards to the miniatures!

The miniatures – classical elegance

For my skirmish forces I plan to use almost exclusively the offerings of Agema Miniatures. I very much enjoy the look of these miniatures with more realistic proportions than other metal or plastic ranges. They have a certain classical elegance to them which reminds me of Greek and Roman sculpture. Victrix have a splendid range of Carthaginians, Iberians and Republican Romans. I might resort to some of their packs for added variety.

I got myself some Velites, Hastati, Principes and Triarii as well as a set of metal heads to convert them into Hannibal’s Veterans. The miniatures are well suited for conversion work and sprues can be easily combined.

Farm Animals

Naturally some scenarios will also require some farm animals such as cows, sheep or chicken. Here the excellent Pegasus set of farm animals comes in handy. Nominally 1:48 it matches the 28mm scale very well. The animals are beautifully sculpted and will also be suitable to add life to a village scene.

I hope you found this introduction to my new project interesting and inspiring. If you have any comments or suggestions feel free to comment below. See you for part II when we start construction of the profiles.

References:

Primary sources:

Cato. De Agricultura. Loeb Classical Library edition. W. D. Hooper and H. B. Ash [Trans.]. 1934.

Columella. De re rustica. Loeb Classical Library edition: Vol. I (Books 1-4). H. B. Ash. [Trans.]. 1941.

Pliny the Elder. The Natural History. J. Bostock, F.R.S. H.T. Riley [Trans.]. London: Taylor and Francis, 1855.

P. Ovidius Naso. Metamorphoses. Arthur Golding [Trans.]. London: W. Seres, 1567.

P. Ovidius Naso. Ovid’s Art of Love (in three Books), the Remedy of Love, the Art of Beauty, the Court of Love, the History of Love, and Amours. Anne Mahoney [Trans.]. New York: Calvin Blanchard, 1855.

Secondary literature:

Becker, J. A. (2013). Villas and Agriculture

in Republican Italy (pp. 309-322). In J. DeRose Evans (ed.), A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic. Blackwell Publishing.

Fuentes-Utrilla, P. , López-Rodríguez, R. A. and Gil, L. (2004). The historical relationship of elms and vines. Invest Agrar: Sist Recur For, 13 (1), 7-15.

Fascinating, I didn’t know about the viticulture! And your terrain project leaves me in awe as always… looking forward to reading more.

Thank you for your comment mon capitan. Glad you enjoyed reading about wine making. I enjoy the end product as well. Would be interesting to create a true Roman vintage with all the additives they put in. I recall ash and sap. A small side dish of pulmentum or bread with garum and I will just feel like in ancient Rome. I hope it works out as I envision it. As long as the modules fit I think not much can go wrong, but I shall regret writing this ;).

Fantastic project. Takes me back to to when I read Ovid too!

Thank you for your comment. Ovid makes some good reading. The 1567 translation might be a bit heavy for me as a non-native speaker, but I enjoyed the 1855 one. If my latin would be up to the task it would be great to just read it in the original, but that will need to wait until I have time to refresh it (retirement project 😀 ?)

Exciting project! I have no doubt that the end product will be drop dead gorgeous. Those plastic miniatures look fantastic, as well.

I was aware of some of the sympathetic planting strategies that existed before the rise of industrialized agriculture, but had never heard of vines and elmes abiding together! Fascinating article, all around. Thanks for sharing your knowledge.

Thanks Arkie, I hope so too. Glad you like the miniatures. They are very nice indeed. can’t wait until they release some Spaniards and Italian allies! I love those helmets and three disc pectorals. Before I had a look at Pliny I was not aware of it either. A pity really, it makes for a truely romantic countryside. A supplier of organic wine should take it up again to add to the mystery :P. Imagine the label, it could have ‘vintage’, ‘whimsical’ and ‘heritage’ all in one sentence!

Don’t forget ‘bespoke!’

Let’s see: “Our bespoke heritage vintage evokes whimsical memories of days long past. It has a subtle taste of Hannibal’s genius and Scipios excellence.” I guess I would buy a bottle. 😉

Hahahah! Marketing via the ancients. Sounds like at LEAST a $20 bottle of wine.

I’m looking forward to see how the project progresses. I’m particularly in treated in seeing how the laser cutting turns out. Getting the sections cut out to a uniform size has always been the most difficult part for me when making modular boards. The miniatures are already looking quite nice.

Hi Brian, thank you for chiming in. I am quite curious how this will work out, too. Some of the HIPS will melt in the process, so I hope it will not affect the accuracy of the pieces. I also have to account for the fact that two sides will be 2mm shorter to take the material thickness into account. That will influence the profile, so I have to make sure I do it properly the first time.

Looking forward to your work. I have found fixing the walls to the boards works and anything bigger needs to be removable. Also a cunning plan is to use Google earth street view to get the feel right at ground level. Saying that I am not sure street view covers the areas of the Punic wars ?

Thank you for the feedback. I think you are right with the built structures. If I magnetise them they might still hover if I do not account for them on a module. I could try to have a flattish area with scarce growth and see if it works. A gaming colleague made use of this with a village terrain piece, however hiding the “slots” where the houses / villa slots in will be the tricky part.

Whatever you do it will look fantastic😀

Certainly an ambitious project. I look forward to seeing many updates as it starts to take shape. I wonder if it might be easier in the long run to make 6 modules for a 6×4 (or even 8, depending on your setup) so that you can maintain consistency throughout the production?

Thank you for commenting. I thought about it, but as it happens I have just enough material for four modules. I also plan to change countries and it took me 3 years to get through the styrofoam I bought back then. So in the end this will make use of my remaining supplies and will be light enough a setup for easy (and cost effective) shipping. It is true that down the road I could run into the problem of making new modules compatible, but I hope my notes on the blog will help me remembering how I finished them.

Change countries? You mean you’re moving internationally/leaving NZ?

Indeed. Better job opportunities in Europe and finishing my studies here necessitate to close a chapter and begin a new one. 🙂 Another positive aspect is that hobby supplies will be easier to procure in Europe.