Hannibal’s Numidian cavalry was famed for its performance in battle, but also very apt in small-scale operations. During the battle of Cannae their conduct made victory for Hannibal possible, yet at Zama them changing sides helped along with his demise.

A Later Carthaginian army is unthinkable without them and in many rule systems they are an obligatory element of the army list. I decided to use Corvus Belli for my Numidian contingent and can say I don’t regret it.

I shall give an overview of the historical background of these fabled riders and some thoughts about painting the Corvus Belli miniatures.

Historical Background

Numidia was an ancient Libyan kingdom in northern Africa, located west of Carthage and spanning what is now Algeria and the western part of Tunisia. Eastern Numidia was seen by contemporary authors as the territory of the Massylii tribe, while the western part was the zone of influence of the Masaesyli tribe. During the Second Punic War king Syphax of the Masaesyli first aligned with Rome, but changed sides after 206 BCE. In the east, however, Masinissa, whose father king Gala had been allied with Carthage, joined forces with Rome.

After Hannibal’s defeat at Zama and the resulting end of the war Masinissa’s strategy paid off: He was given all of Numidia to rule, which he accomplished up untill his death in 148 BCE. Decades later Jugurtha came into power and provoked Rome resulting in a long, drawn out war. This conflict ultimately led to a dependency of Numidia on Rome as well as being the scene of a number of battles during the civil war. After this conflict Numidia was transformed into a Roman province.

The Berber people of Numidia

The Berber people of Numidia were famed for their excellent horsemanship and provided both the Roman and Carthaginian army with contingents of light cavalry, but also light skirmishers. As Strabo (17.3.8) describes they were riding their small horses bareback, using only a simple rope around their horse’s neck to direct it. They were experts in fast hit and run manoeuvres harassing their opponents with javelins made of burnt wood (cf. Hdt. 7.71) only to retreat to avoid a counter attack. Being dressed in a simple, belted or unbelted tunic and only having a shield covered in hide as a defensive weapon, they had to rely on their speed and skill (Strabo 17.3.8).

During the first Punic war this tactic is best illustrated by an incident reported by Polybios during the siege of Agrigentum in Sicily in 261 BCE:

He [Hanno, commander of the Carthaginian relief force] saw that the Romans were reduced by disease and want, owing to an epidemic that had broken out among them, and he believed that his own forces were strong enough to give them battle: he accordingly collected his elephants, of which he had about fifty, and the whole of the rest of his army, and advanced at a rapid pace from Heracleia; having previously issued orders to the Numidian cavalry to precede him, and to endeavour, when they came near the enemies’ stockade, to provoke them and draw their cavalry out; and, having done so, to wheel round and retire until they met him. The Numidians did as they were ordered, and advanced up to one of the camps. Immediately the Roman cavalry poured out and boldly charged the Numidians: the Libyans retired, according to their orders, until they reached Hanno’s division: then they wheeled round; surrounded, and repeatedly charged the enemy; killed a great number of them, and chased the rest up to their stockade.

Plb. 1.19

They played an even more important role during the famous battle of Cannae in 216 BCE during the Second Punic War. While Hannibal’s crushing victory relied on all elements of his army working together, it were the Numidians in combination with Iberian and Celtic cavalry that drove off the Roman cavalry and allowed to deal the final blow to the Roman force:

On his left wing, close to the river, he [Hannibal Barcas] stationed the Iberian and Celtic horse opposite the Roman cavalry; and next to them half the Libyan heavy-armed foot; and next to them the Iberian and Celtic foot; next, the other half of the Libyans, and, on the right wing, the Numidian horse. Having now got them all into line he advanced with the central companies of the Iberians and Celts; and so arranged the other companies next these in regular gradations, that the whole line became crescent-shaped, diminishing in depth towards its extremities: his object being to have his Libyans as a reserve in the battle, and to commence the action with his Iberians and Celts.

[…]

The battle was begun by an engagement between the advanced guard of the two armies; and at first the affair between these light-armed troops was indecisive. But as soon as the Iberian and Celtic cavalry got at the Romans, the battle began in earnest, and in the true barbaric fashion: for there was none of the usual formal advance and retreat; but when they once got to close quarters, they grappled man to man, and, dismounting from their horses, fought on foot. But when the Carthaginians had got the upper hand in this encounter and killed most of their opponents on the ground,— because the Romans all maintained the fight with spirit and determination,—and began chasing the remainder along the river, slaying as they went and giving no quarter; then the legionaries took the place of the light-armed and closed with the enemy.

For a short time the Iberian and Celtic lines stood their ground and fought gallantly; but; presently overpowered by the weight of the heavy-armed lines, they gave way and retired to the rear, thus breaking up the crescent. The Roman maniples followed with spirit, and easily cut their way through the enemy’s line; since the Celts had been drawn up in a thin line, while the Romans had closed up from the wings towards the centre and the point of danger. For the two wings did not come into action at the same time as the centre: but the centre was first engaged, because the Gauls, having been stationed on the arc of the crescent, had come into contact with the enemy long before the wings, the convex of the crescent being towards the enemy.

The Romans, however, going in pursuit of these troops, and hastily closing in towards the centre and the part of the enemy which was giving ground, advanced so far, that the Libyan heavy-armed troops on either wing got on their flanks. Those on the right, facing to the left, charged from the right upon the Roman flank; while those who were on the left wing faced to the right, and, dressing by the left, charged their right flank,1 the exigency of the moment suggesting to them what they ought to do. Thus it came about, as Hannibal had planned, that the Romans were caught between two hostile lines of Libyans—thanks to their impetuous pursuit of the Celts. Still they fought, though no longer in line, yet singly, or in maniples, which faced about to meet those who charged them on the flanks.

The Numidian horse on the Carthaginian right were meanwhile charging the cavalry on the Roman left; and though, from the peculiar nature of their mode of fighting, they neither inflicted nor received much harm, they yet rendered the enemy’s horse useless by keeping them occupied, and charging them first on one side and then on another. But when Hasdrubal, after all but annihilating the cavalry by the river, came from the left to the support of the Numidians, the Roman allied cavalry, seeing his charge approaching, broke and fled.

At that point Hasdrubal appears to have acted with great skill and discretion. Seeing the Numidians to be strong in numbers, and more effective and formidable to troops that had once been forced from their ground, he left the pursuit to them; while he himself hastened to the part of the field where the infantry were engaged, and brought his men up to support the Libyans. Then, by charging the Roman legions on the rear, and harassing them by hurling squadron after squadron upon them at many points at once, he raised the spirits of the Libyans, and dismayed and depressed those of the Romans.

Plb. 3.113-3.116

Finally, the Numidians were also excellent in smaller engagements and operations, for instance in rounding up survivors after the battle:

While this struggle and carnage were going on, the Numidian horse were pursuing the fugitives, most of whom they cut down or hurled from their horses […] In like manner the Numidian horse brought in all those who had taken refuge in the various strongholds about the district, amounting to two thousand of the routed cavalry.

Plb. 3.116-3.117

There are many other reports featuring the Numidian light cavalry, and they were often used for ambushes (Plb. 3.68) or routing the enemy’s camp (Plb. 3.71).

Painting the Numidians

There are no contemporary figurative depictions of Numidian Cavalry of the Second Punic War, yet we have an earlier relief fragment, that ostensibly adorned a so called sphagia (funnel-shaped jug), showing a wounded Numidian horseman. It is dated to the 4th and 3rd century BCE and can be seen at the Louvre.

A much later scene on Trajan’s column might depict Moorish or Numidian light cavalry fighting. It seems Corvus Belli based the miniatures on this depiction, which seems reasonable comparing it to Polybios’ and Strabo’s written accounts.

I went for a simple colour scheme that is based on educated guesses. The tunics are painted in an off-white or sand tone, washed brown and then highlighted with succeedingly lighter shades of the off-white or sand base colour.

According to Herodotos Numidian women wore cloaks made of goatskin and a “hairless tasselled ‘aegea’ over their dress, colored with madder” (4.189) αἰγίς being the greek term for goatskin. Herodotos is not always reliable, but in this case his description seems coherent with regard to materials and colour. This would first suggest that madder was readily available and could have been used to dye not only leather equipment, but also fabric. It is also possible that goatskin or leather attire was used by men in some form or shape, as it is once again suggested by Herodotos when describing Xerxes’ Numidian contigents in his Histories (Hdt. 7.71). I don’t think any of the Corvus Belli miniatures are depicted with a goatskin or leather dress, but having red as an alternative colour is a nice option.

For the skin tone I mixed some brown into my usual skin base colour to achieve an olive skin tone.

To add a bit of variety I used three different shades for the horses: medium brown, beige and sand in combination with different markings.

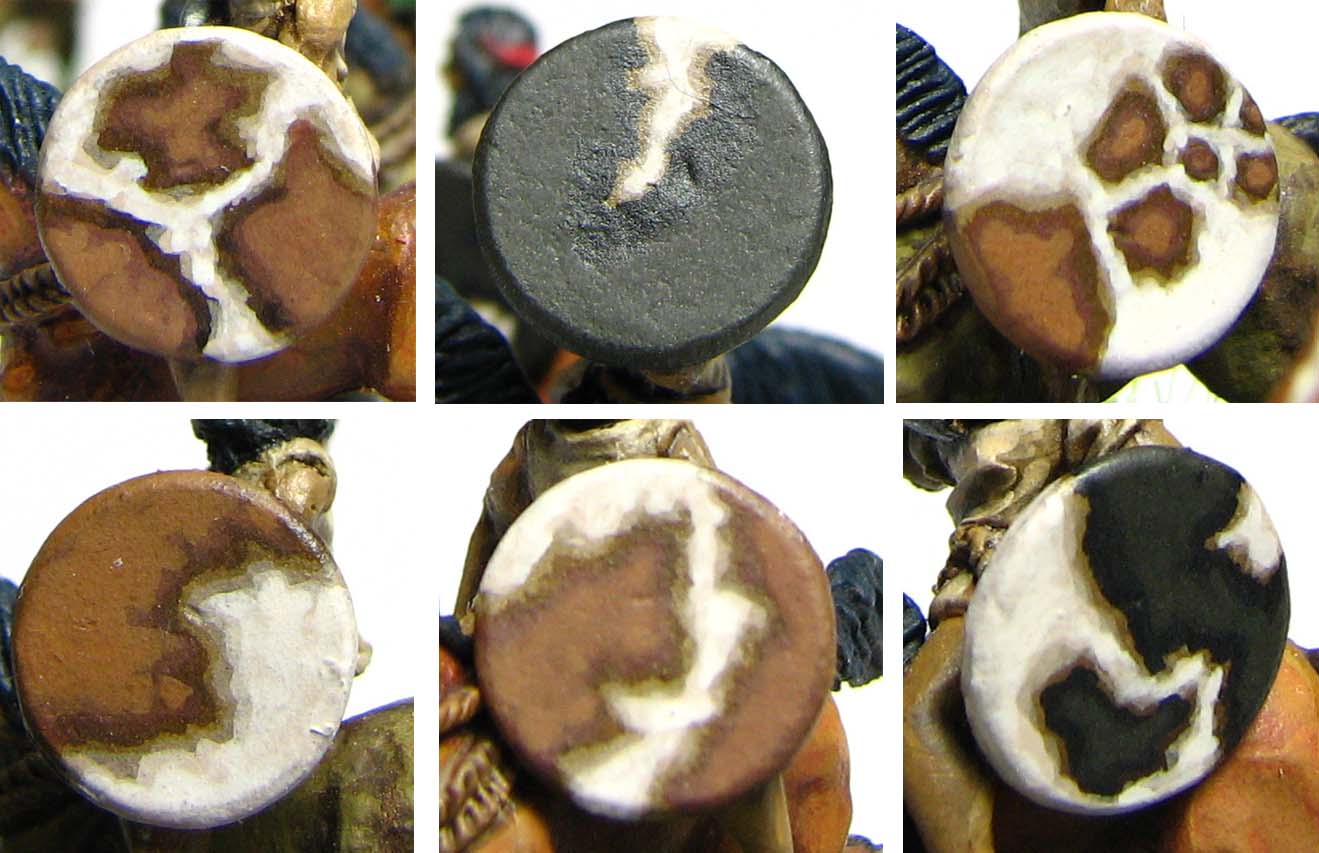

Finally the shields were painted resembling animal hide, featuring all unique freehand designs.

I hope you enjoyed this introduction to the Numidian Light cavalry and might even be inspired to get some on your own, may it be in 15mm or any other scale. If you have suggestions or anything fascinating to add to the history of these troops please feel free to do so.

References:

The Geography of Strabo. Literally translated, with notes, in three volumes. London. George Bell & Sons. 1903.

Histories. Polybius. Evelyn S. Shuckburgh. translator. London, New York. Macmillan. 1889. Reprint Bloomington 1962.

Stop tempting me to turn my Numidian auxiliaries into a Numidian army!

Give in to temptation! Think of all the elephants you could have and imitation legionaries! ;D

Excellent research, can’t fault it especially since I came to the same conclusions but with less research and nowhere near as good shields- brilliant! Might need to upgrade my Numidians as they are over 20 years old and look dated in comparison, but still one of the best troop types!

Thank you Paul. glad you like the article. I would not call them the best, but maybe the most flexibel, at least in FoG ;).

THOSE SHIELDS! O_o Your freehand animal hide is made of WIN (not a sentence I ever thought I would utter).

Also, as always I love your dynamic little captioned scenes. I pity the Romans, really. About to be harassed and all…

I see I did not reply to this comment. Shame on me. Thank you nevertheless. Wargaming always leads to strange sentences uttered and even stranger topics to be discussed (hour long discussions about elephant turrets might ensue at any given time), but hey, that is one of the pleasant aspects of it ;).

Great stuff here. I love the ‘scenic’ photos. The shields are also magnificent. Lots of times, painters make the ‘hides’ all look the same. Im sure ancients used whatever hides they could get their hands on. Nicely done.

Thank you very much. Putting together the ‘scenic’ photos is very enjoyable indeed. I really wanted to add variety, to spice up the rather muted colours. A red headband here and there also helps to achieve this :).

Very nice work (and nice write-up). I especially like the freehand work on those shields as well as your photography of the figures. I didn’t know Corvus Belli did historicals – I thought they only made figures for Infinity for some reason…

Thank you, glad you like them. I think they started out with historicals, but then left it at the existing ranges and never expanded them. Infinity surely sold much more units. Still, they are some of the best 15mm miniatures out there. The Forged in Battle range will add another excellent line of Ancients, soon.

That was a great introduction to the unit-you’re especially to be commended for using references. It’s real history! On a wargaming blog! 🙂

The figures look great (especially the shields and skin tone). I’m sure they’ll serve you well on the battlefield. Or not, if your luck with new units is anything like mine.

Thanks! It’s the degree in Ancient history that makes me go for the primary sources :P. Might be a good thing there is no footnote function in wordpress…

They did perform well once, but I had mixed results all the other times. Being on a flank march they never arrived or they just left the table. However, in their hour of glory they were able to reach an already committed battle group in the rear, helping with their eventual demise and me winning the game. I guess they won me over that day. 😉

I say bring on the footnote plugin, so you can get to work. 🙂

Excellent story about your Numidians-that’s the sort of thing you remember for years, and helps give the unit a bit of an identity.

That was really interesting and informative. You did a great job on the shields. The muted colors make the riders appear so lifelike. Beautiful miniatures, beautiful post.

Thank you. Given the project is now in its 4th year painting styles did change quite a bit. I do like muted colours in general, but did also experiment with taking the highlights a step further. If I finally finish the Celtiberian cavalry this slight change in approach will be more clear.

Great post! Funnily enough, I’ve been thinking of doing the Punic Wars in 15mm lately… I’ve been a fan of Hannibal since I read about him as a child. And who could resist elephants? On the other hand, I don’t need another project – but who does 🙂

Thank you! Now is the time to do so! Forged in Battle will soon release its superb 15mm Ancients range and I suspect they will mix up nicely with Corvus Belli for variety.

With the broad selection of troop types and their charismatic leader the Later Carthaginans are really a beautiful army. Oh, and yes I am a big fan of war elephants on the gaming table.

Hannibal in my view is one of the greatest generals ever and mainly down to his ability to combine different races together and get them to fight as a team. Your Numidian cavalry are lovely but where are the slingers ? The slingers were legendary 🙂

I agree. 😉 I have some Balearic slingers in my army, but no Numidian ones. They will be featured in one of the next posts. 🙂